笠井叡 舞踏をはじめて <13>

Akira Kasai Begins Butoh <13>

Akira Kasai studied under Kazuo Ohno, interacted with Tatsumi Hijikata, and gave birth to the word "butoh". He will talk about his life and his own butoh.

In January 1976, I held a solo recital “Tsukiyomi Hiruko”. This was followed by the presentation of four solo works.

After Tenshikan was established, I began to present more group dance works as Tenshikan performances. The most representative of these works was “Seven Seals,” followed by “Denju no Mon” the following year. I returned to a full-fledged solo form again with “Tsukiyomi Hiruko”. That year, I gave four solo performances in one year: “Tristan and Isolde” in March, “For the Dance of the Holy Spirit as an Individual esoteric ritual” in September, and “The Future of Matter” in December.

In the 1970s, when I was creating stages with Mr. Kazuo Ohno and Mr. Hijikata, I did not receive any state subsidies. This was a great feature; I was creating stages with my own personal money. The first time I created my own stage was during my junior year of college, and it made a loss of hundreds of thousands of yen at the time. For a student, that was quite a big burden, so I could only perform once a year.

It was not the era of monthly stage productions, as is the case today, but rather, I concentrated on producing only one day performance a year. In this day and age, however, it is customary to start with the negotiation of fees. Nothing new can ever come from such circumstances. Dance that begins with national money or a grant to put on a performance may or may not exist. It was like unworthy to me. Until I went to Germany, purity was the only thing on which I hung my hat.

Every time I gave a solo performance, I was making a huge loss, and the more I performed, the more I went into debt. The Tenshikan group dance performances were often packed, but just because there were people in the audience did not mean there was money to be made. In any case, it was difficult to make money from my stage work, and my income from cabaret shows and workshops was my living. But with “Tsukiyomi Hiruko,” I was able to make a profit for the first time. I did not consciously set out to make a profit, though.

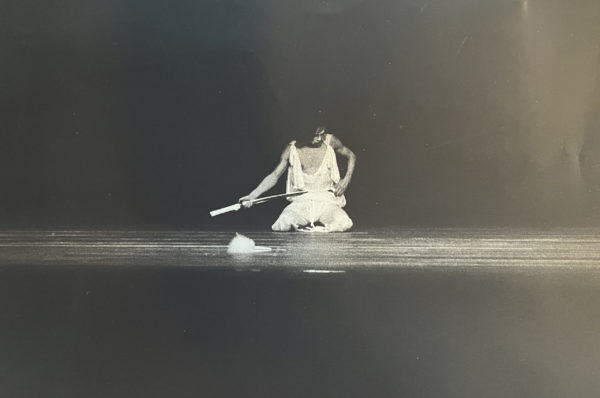

In “Tsukiyomi Hiruko,” I dance with a Japanese sword as a tribute to Mr. Mishima, who committed suicide by harakiri in 1970. I have always had the question in my mind, “Why did Mr. Mishima use a Japanese sword?” He committed suicide by harakiri with a Japanese sword. This was not only the end of his life, but also a way for him to settle all political situations surrounding Japan. The Japanese sword is a spiritual symbol of Japanese men, and I think some people considered it more important than themselves.

Including these meanings, I initially thought of making a dance out of Mr. Mishima's tetralogy “The Sea of Fertility,” the last work before his death, and titled it “Tenjin Gosui” (The Five Declines of Men). I thought that I would be able to capture the issues of Japanese swords and culture, as well as Mr. Mishima's body, to some extent.

One night, however, Hisako, my wife, jumped up and said, “I had a dream about Mr. Mishima. In the dream, Mr. Mishima was extremely angry”. Hearing this, I began to wonder, “Could it be that he didn't want his work to be titled in this way?” I called Mr. Mishima's wife, Yohko Hiraoka, and told her, “Actually, I would like to do a dance performance under the title of ‘Tenjin Gosui’” to which she replied with some puzzlement, “No, that is still a bit of a problem”. I thought that would certainly be the case, so I changed the title to “Tsukiyomi Hiruko” instead of “Tenjin Gosui” (The Five Declines of Men).

Rather than dedicating “Tsukiyomi Hiruko” to Mr. Mishima, it was more of my own imagination of the Japanese sword that I felt through him on stage. I held the same Japanese sword as I did in “Tannhäuser” and created various improvisational dances. Simply put, it is a Japanese sword dance. Because it was done with a real sword, I think it had a certain intensity for the audience. The performance lasted about an hour and a half. I tend to use a lot of costumes, and in “Tannhäuser” I danced in five or six different costumes, but in “Tsukiyomi Hiruko” I hardly changed my costume at all and just danced with a Japanese sword in my hand.

On the flyer for “Tsukiyomi Hiruko,” I included the words, “Thank you to Mishima”. When Mr. Hijikata saw it, he got into a lot of trouble with me, saying, “Why are you thanking Mishima?” I don't think Mr. Hijikata had any sense of gratitude to Mr. Mishima. But I am sure that Mr. Mishima was one of the most important persons to Mr. Hijikata. From my point of view, Mr. Mishima, Mr. Hijikata, and Mr. Shibusawa had such a special relationship that no one else could intervene in. These three people had different physical characteristics, and they were all connected to each other on that basis.

Mr. Hijikata is a person who can express something of himself through dance without using words. Perhaps there was a part in Mr. Mishima that made Mr. Hijikata feel fear in some way. On the other hand, Mr. Mishima was a person who had physicality that dancers do not have, such as being trained in kendo and karate. I think Mr. Hijikata had a certain sense of fear and respect for Mr. Mishima, who is a literary scholar but has the same deadly body as himself.

Mr. Shibusawa is also a person who had a certain kind of physicality that dancers cannot reach. He always said, “My body doesn't need any training. The best state of my body is to be an infant's body. The best state of my body is to be an infant's body and to be enfant terrible”. He thought that it is enough to have the purest body of a child, which neither Mr. Hijikata nor Mr. Mishima had.

In fact, Mr. Shibusawa was a carefree natural child, and he was enfant terrible himself. Mr. Shibusawa is a very cheerful and healthy person, and he professed, “I have never dreamed of evil spirits of mountains and rivers or other mysterious dreams. I have always seen only blue skies.” That must be why he was so absorbed in the world of monsters and demons. Mr. Shibusawa is not trying to be innocent, but he was always an innocent person. No one can beat this innocence, and everyone is OK when they are in front of Mr. Shibusawa. Mr. Shibusawa had an angelic innocence. Such a body can never be created by training.

I had felt that there was something in common between these three people. However, the relationship changed when Mr. Mishima committed harakiri. I am sure that Mr. Hijikata had many complicated feelings. He may have felt that he could not use words like “thank you” to express his feelings.

The people I have met by chance are irreplaceable to me. I have published some form of connection with them in my work “Tsukiyomi Hiruko” for Mr. Mishima and in my later work “The Voyage of the Prince of Takaoka” for Mr. Shibusawa. In that sense, it was “The Sick Dancing Princess/Visionary Landscape of Tatsumi Hijikata” that brought out Mr. Hijikata as a theme for the stage. I did not dedicate it to him, I just created the work based on my own selfish feelings, but it was my own way of connecting with Mr. Hijikata, and this work was the only one that allowed me to connect with him in a tangible way. It took me a long time to turn it into a work of art, though.

Continue to Akira Kasai Begins Butoh <14>.

Profile

Butoh dancer and choreographer, who became friends with Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno at a young age in the 1960s, and gave numerous solo butoh performances mainly in Tokyo and elsewhere. In the 1970's, operated Tenshikan Butoh dance school where he trained numerous butoh dansers. From 1979 to 1985, studied abroad to study in Germany.Studied Rudolf Steiner's anthroposophy and eurythmy. After returning to Japan, he did not perform on stage and was away from the dance world for 15 years, but returned to the stage with "Seraphita". Since then, he has given numerous performances in Japan and abroad, and has been praised as "the Nijinsky of Butoh". His masterpiece "Pollen Revolution" was performed in various cities around the world. He has created works in Berlin, Rome, New York, Angers, the Centre National de Danse Contemporaine de France, and elsewhere. https://akirakasai.com